Japanese internment, World War II

2011-02-21 13:54:18

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians were widely suspected as supporters of the aggressive militarism of the Japanese Empire. Despite the absence of any evidence of sabotage or espionage, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the forcible internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom had been born in the United States. In the same month, the Canadian government ordered the expulsion of 22,000 Japanese Canadians from a 100-mile strip along the Pacific coast.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the U.S. Congress passed the Alien Registration Act (1940), requiring all non-naturalized aliens aged 14 and older to register with the government and tightening naturalization requirements. With the U.S. declaration of war against Germany, Italy, and Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor, more than 1 million foreign-born immigrants from those countries became “enemy aliens.” Italians and Germans were so deeply assimilated into American culture, however, that they were largely left alone. More visibly distinct and ethnically related to the attackers, Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent were quickly targeted in the early-war hysteria. The territory of Hawaii was put under military rule, and the 37 percent of its population of Japanese ancestry was carefully watched, though they were not interned or evacuated. On the mainland, many politicians and members of the press, along with agricultural and patriotic pressure groups, urged action against the Japanese, leading to Executive Order 9066, empowering the War Department to remove people from any area of military significance.

Japanese Americans were forced to dispose quickly of their property, usually at considerable loss. They were often allowed to take only two suitcases with them. Internmentcamp life was physically rugged and emotionally challenging. Most nisei, or second-generation Japanese in the United States, thought of themselves as thoroughly American and felt betrayed by the justice system. They nevertheless remained loyal to the country, and eventually more than 33,000 served in the armed forces during World War II. Among these were some 18,000 members of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which became one of the most highly decorated of the war. Throughout the war, about 120,000 were interned under the War Relocation Authority in one of 10 hastily constructed camps in desert or rural areas of Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Arkansas, Idaho, California, and Wyoming. In three related cases that came before the Supreme Court—Yasui v. United States (1942), Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), and Korematsu v. United States (1944)—the government’s authority was upheld, though a dissenting judge noted that such collective guilt had been assumed “based upon the accident of race.” The camps were finally ordered closed in December 1944. The Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 provided $31 million in compensation, though this was later determined to be less than one-10th the value of property and wages lost by Japanese Americans during their internment. In Canada, the government bowed to the unified pressure of representatives from British Columbia, giving the minister of justice the authority to remove Japanese Canadians from any designated areas. While their property was at first impounded for later return, an order-in-council was passed in January 1943 allowing the government to sell it without permission and then to apply the funds to the maintenance of the camps. With labor shortages by 1943, some Japanese Canadians were allowed to move eastward, especially to Ontario, though they were not permitted to buy or lease lands or businesses. Though it was acknowledged that “no person of Japanese race born in Canada” had been charged with “any act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war,” the government provided strong incentives for them to return to Japan. After much debate and extensive challenges in the courts, more than 4,000 returned to Japan, more than half of whom were Canadian-born citizens. More than 13,000 of those who stayed left British Columbia, leaving fewer than 7,000 in the province.

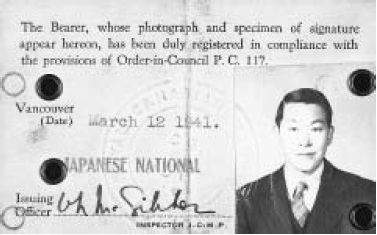

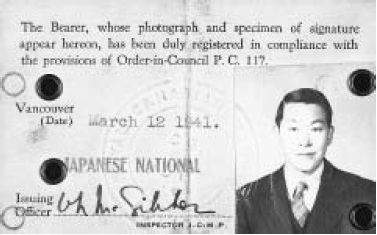

This photo shows the front of Sutekichi Miyagawa’s internment identification card issued by the Canadian government in compliance with Order-in-Council P.C. 117, Vancouver, British Columbia, March 12, 1941. During World War II, some 120,000 Japanese Americans and 22,000 Japanese Canadians were interned or relocated. (National Archives of Canada)

In 1978, the Japanese American Citizens’ League formed the National Committee for Redress, spearheading efforts for a formal apology and compensation for survivors. In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens (CWRIC). After 18 months of investigations, the commission issued its final report in 1983, concluding that “a grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese descent.” No documented case of sabotage or disloyalty by a Japanese American was found, and it was discovered that the Justice and War Departments had altered records and thereby misled the courts. After a further five years of negotiation, in 1988, the Civil Liberties Act was signed by President Ronald Reagan, who noted that Japanese Americans had proven “utterly loyal,” providing an apology and $20,000 to each camp survivor still living. The eventual payout was more than $1.6 billion. Less than two weeks later, the Canadian government publicly apologized and provided compensation, including $12,000 to each survivor, a $12 million social and educational package for the Japanese community, and a further $12 million to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the U.S. Congress passed the Alien Registration Act (1940), requiring all non-naturalized aliens aged 14 and older to register with the government and tightening naturalization requirements. With the U.S. declaration of war against Germany, Italy, and Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor, more than 1 million foreign-born immigrants from those countries became “enemy aliens.” Italians and Germans were so deeply assimilated into American culture, however, that they were largely left alone. More visibly distinct and ethnically related to the attackers, Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent were quickly targeted in the early-war hysteria. The territory of Hawaii was put under military rule, and the 37 percent of its population of Japanese ancestry was carefully watched, though they were not interned or evacuated. On the mainland, many politicians and members of the press, along with agricultural and patriotic pressure groups, urged action against the Japanese, leading to Executive Order 9066, empowering the War Department to remove people from any area of military significance.

Japanese Americans were forced to dispose quickly of their property, usually at considerable loss. They were often allowed to take only two suitcases with them. Internmentcamp life was physically rugged and emotionally challenging. Most nisei, or second-generation Japanese in the United States, thought of themselves as thoroughly American and felt betrayed by the justice system. They nevertheless remained loyal to the country, and eventually more than 33,000 served in the armed forces during World War II. Among these were some 18,000 members of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which became one of the most highly decorated of the war. Throughout the war, about 120,000 were interned under the War Relocation Authority in one of 10 hastily constructed camps in desert or rural areas of Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Arkansas, Idaho, California, and Wyoming. In three related cases that came before the Supreme Court—Yasui v. United States (1942), Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), and Korematsu v. United States (1944)—the government’s authority was upheld, though a dissenting judge noted that such collective guilt had been assumed “based upon the accident of race.” The camps were finally ordered closed in December 1944. The Evacuation Claims Act of 1948 provided $31 million in compensation, though this was later determined to be less than one-10th the value of property and wages lost by Japanese Americans during their internment. In Canada, the government bowed to the unified pressure of representatives from British Columbia, giving the minister of justice the authority to remove Japanese Canadians from any designated areas. While their property was at first impounded for later return, an order-in-council was passed in January 1943 allowing the government to sell it without permission and then to apply the funds to the maintenance of the camps. With labor shortages by 1943, some Japanese Canadians were allowed to move eastward, especially to Ontario, though they were not permitted to buy or lease lands or businesses. Though it was acknowledged that “no person of Japanese race born in Canada” had been charged with “any act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war,” the government provided strong incentives for them to return to Japan. After much debate and extensive challenges in the courts, more than 4,000 returned to Japan, more than half of whom were Canadian-born citizens. More than 13,000 of those who stayed left British Columbia, leaving fewer than 7,000 in the province.

This photo shows the front of Sutekichi Miyagawa’s internment identification card issued by the Canadian government in compliance with Order-in-Council P.C. 117, Vancouver, British Columbia, March 12, 1941. During World War II, some 120,000 Japanese Americans and 22,000 Japanese Canadians were interned or relocated. (National Archives of Canada)

In 1978, the Japanese American Citizens’ League formed the National Committee for Redress, spearheading efforts for a formal apology and compensation for survivors. In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens (CWRIC). After 18 months of investigations, the commission issued its final report in 1983, concluding that “a grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese descent.” No documented case of sabotage or disloyalty by a Japanese American was found, and it was discovered that the Justice and War Departments had altered records and thereby misled the courts. After a further five years of negotiation, in 1988, the Civil Liberties Act was signed by President Ronald Reagan, who noted that Japanese Americans had proven “utterly loyal,” providing an apology and $20,000 to each camp survivor still living. The eventual payout was more than $1.6 billion. Less than two weeks later, the Canadian government publicly apologized and provided compensation, including $12,000 to each survivor, a $12 million social and educational package for the Japanese community, and a further $12 million to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

- People

- Immigrant groups

- Labor

- Nativism

- Civil rights and liberties

- Cities

- Culture

- Refugees and displaced persons

- Court cases

- Illegal immigration

- Advocacy organizations and movements

- Health

- Arts and music

- European immigrants

- Anti-immigrant movements and policies

- African immigrants

- Citizenship and naturalization

- States

- Asian immigrants

- Agricultural workers

- Children

- Immigration reform

- Laws

- East asian immigrants

- Borders

- Deportation

- Events and movements

- International agreements

- Mexican immigrants

- Education

- Emigration

- Theories

- Ethnic enclaves

- Latin american immigrants

- Business

- Science and technology

- Government agencies and commissions

- Politics and government

- Family issues

- Women

- Economic issues

- Southeast asian immigrants

- Canadian immigrants

- Push-pull factors

- Transportation

- Slavery

- Philanthropy

- Religion

- Demographics

- Research

- Assimilation

- Literature

- Subversive and radical political movements

- Communications

- Journalism

- Language issues

- Crime

- Violence

- Military

- Wars

- Law enforcement

- West indian immigrants

- Stereotypes

- Symbols

- Land

- Psychology

- South and Southwest Asian immigrants

- Pacific Islander immigrants

- Colonies and colonial regions

- Legislation and regulations

- Canada

- United States

- War and immigration

- Administration

- Hispanic issues and leaders

- Treaties

- Economics and commerce

- Immigration policy

- Religion

- Colonial founders and leaders

- Explorers and geographers

- France

- Political figures: Canada

- Political figures: United States

- Race and ethnicity

- Reformers, activists, and ethnic leaders

- Women