Alexander Graham Bell

2011-06-27 02:03:43

Identification: Scottish American inventor and educator

Born: March 3, 1847; Edinburgh, Scotland

Died: August 2, 1922; Baddeck, Nova Scotia

Significance: Entering the United States at the invitation of a Boston institution and speaking excellent English, Bell may not have thought himself an immigrant until his first attempt to patent his telephone was rejected on the grounds that he was an alien. Once naturalized, Bell proudly proclaimed himself an American citizen.

Alexander Graham Bell’s grandfather taught correct pronunciation and elocution, as did Bell’s father, Alexander Melville Bell. Young Bell became adept at teaching “Visible Speech,” the system of symbols his father invented showing the positions of the lips, tongue, and soft palate needed to reproduce all sounds. In May, 1868, Bell used Visible Speech for the first time to teach the deaf to speak English.

After both of Bell’s brothers died of tuberculosis, his father moved the family to the more healthful climate of Canada, settling at Brantford, Ontario, in August, 1870. When the Boston School for the Deaf invited Bell’s father to teach Visible Speech there, he sent his son instead. There were then no requirements that Bell hold a passport or have a visa to enter the United States, and Bell did not think himself an immigrant in March, 1871, when he traveled forty-five miles east to Buffalo, New York, and casually boarded a through train to Boston.

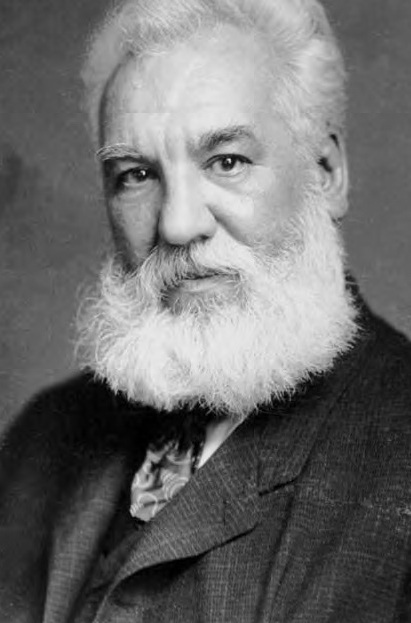

Alexander Graham Bell around 1902. (Library of Congress)

Bell found the city congenial, teaching at the School for the Deaf, becoming professor of vocal physiology and elocution at Boston University, and privately tutoring deaf students, including Mabel Hubbard, who later became his wife. He experimented at night, seeking a way to transmit speech over an electric wire. Bell was rudely awakened to his alien status when he tried to file a caveat (notice of intention to file a patent) with the United States Patent Office to establish priority as the inventor of the telephone. Told that, although aliens were eligible to apply for patents, only citizens could file caveats, Bell began the process of naturalization. He took out his first papers in 1874, which granted him most rights of citizens, except the right to vote. He did not complete the process and become a full citizen until November 10, 1882, by which time he had patented the telephone (1876) and moved to Washington, D.C., where he still could not vote in presidential elections.

Bell and his wife honeymooned in Great Britain, where his wife became pregnant and gave birth to their first daughter. Her birth there made the daughter technically a dual British American citizen, as was her father; British law counted all born in Britain as subjects of Queen Victoria for life. Because wives assumed the status of husbands under both British and American law, the entire family could have, but did not, consider themselves dual nationals.

Bell was proud of his American citizenship, specifically rejecting in 1915 the notion that he was a hyphenated American and flying the American flag at his summer home in Nova Scotia. At his instructions, the plaque marking his burial place at his Canadian summer home bears the inscription: “Died a Citizen of the United States.”

Milton Berman

Further Reading

Born: March 3, 1847; Edinburgh, Scotland

Died: August 2, 1922; Baddeck, Nova Scotia

Significance: Entering the United States at the invitation of a Boston institution and speaking excellent English, Bell may not have thought himself an immigrant until his first attempt to patent his telephone was rejected on the grounds that he was an alien. Once naturalized, Bell proudly proclaimed himself an American citizen.

Alexander Graham Bell’s grandfather taught correct pronunciation and elocution, as did Bell’s father, Alexander Melville Bell. Young Bell became adept at teaching “Visible Speech,” the system of symbols his father invented showing the positions of the lips, tongue, and soft palate needed to reproduce all sounds. In May, 1868, Bell used Visible Speech for the first time to teach the deaf to speak English.

After both of Bell’s brothers died of tuberculosis, his father moved the family to the more healthful climate of Canada, settling at Brantford, Ontario, in August, 1870. When the Boston School for the Deaf invited Bell’s father to teach Visible Speech there, he sent his son instead. There were then no requirements that Bell hold a passport or have a visa to enter the United States, and Bell did not think himself an immigrant in March, 1871, when he traveled forty-five miles east to Buffalo, New York, and casually boarded a through train to Boston.

Alexander Graham Bell around 1902. (Library of Congress)

Bell found the city congenial, teaching at the School for the Deaf, becoming professor of vocal physiology and elocution at Boston University, and privately tutoring deaf students, including Mabel Hubbard, who later became his wife. He experimented at night, seeking a way to transmit speech over an electric wire. Bell was rudely awakened to his alien status when he tried to file a caveat (notice of intention to file a patent) with the United States Patent Office to establish priority as the inventor of the telephone. Told that, although aliens were eligible to apply for patents, only citizens could file caveats, Bell began the process of naturalization. He took out his first papers in 1874, which granted him most rights of citizens, except the right to vote. He did not complete the process and become a full citizen until November 10, 1882, by which time he had patented the telephone (1876) and moved to Washington, D.C., where he still could not vote in presidential elections.

Bell and his wife honeymooned in Great Britain, where his wife became pregnant and gave birth to their first daughter. Her birth there made the daughter technically a dual British American citizen, as was her father; British law counted all born in Britain as subjects of Queen Victoria for life. Because wives assumed the status of husbands under both British and American law, the entire family could have, but did not, consider themselves dual nationals.

Bell was proud of his American citizenship, specifically rejecting in 1915 the notion that he was a hyphenated American and flying the American flag at his summer home in Nova Scotia. At his instructions, the plaque marking his burial place at his Canadian summer home bears the inscription: “Died a Citizen of the United States.”

Milton Berman

Further Reading

- Bruce, Robert V. Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude. Boston: Little, Brown, 1973.

- Grosvenor, Edwin S., and Morgan Wesson. Alexander Graham Bell: The Life and Times of the Man Who Invented the Telephone. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997.

- Shulman, Seth. The Telephone Gambit: Chasing Alexander Graham Bell’s Secret. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

- People

- Immigrant groups

- Labor

- Nativism

- Civil rights and liberties

- Cities

- Culture

- Refugees and displaced persons

- Court cases

- Illegal immigration

- Advocacy organizations and movements

- Health

- Arts and music

- European immigrants

- Anti-immigrant movements and policies

- African immigrants

- Citizenship and naturalization

- States

- Asian immigrants

- Agricultural workers

- Children

- Immigration reform

- Laws

- East asian immigrants

- Borders

- Deportation

- Events and movements

- International agreements

- Mexican immigrants

- Education

- Emigration

- Theories

- Ethnic enclaves

- Latin american immigrants

- Business

- Science and technology

- Government agencies and commissions

- Politics and government

- Family issues

- Women

- Economic issues

- Southeast asian immigrants

- Canadian immigrants

- Push-pull factors

- Transportation

- Slavery

- Philanthropy

- Religion

- Demographics

- Research

- Assimilation

- Literature

- Subversive and radical political movements

- Communications

- Journalism

- Language issues

- Crime

- Violence

- Military

- Wars

- Law enforcement

- West indian immigrants

- Stereotypes

- Symbols

- Land

- Psychology

- South and Southwest Asian immigrants

- Pacific Islander immigrants

- Colonies and colonial regions

- Legislation and regulations

- Canada

- United States

- War and immigration

- Administration

- Hispanic issues and leaders

- Treaties

- Economics and commerce

- Immigration policy

- Religion

- Colonial founders and leaders

- Explorers and geographers

- France

- Political figures: Canada

- Political figures: United States

- Race and ethnicity

- Reformers, activists, and ethnic leaders

- Women