Canadian immigrants

2011-08-24 12:23:01

Significance: Canadian immigration to the United States has historically been episodic, typically paralleling economic fluctuations and shifts in employment opportunities in one or the other of the two neighboring countries. However, during the early twentieth century, many French-speaking Canadians immigrated to the United States to remove themselves from religious and political discrimination.

Immigration into the territory of the future United States from what were once called British North America and French Canada began during the age of exploration and colonization, when international borders were porous. Large-scale migration from French Canada began in 1755, with the expulsion of the Acadian French from Nova Scotia by Great Britain. There was little immigration from British North America after the American Revolution ended in 1783. Immigration to the United States from British North America did not significantly resume until the decade before the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) and continued to increase until 1890. The migration of French Canadians intensified from 1900 until 1930 to fill assembly lines in New England shoe and textile factories. The last major wave of Canadian immigration to the United States occurred between 1940 and 1990, after which Canadian immigration to the United States steadily declined.

Immigration Before 1776

Exploration and colonization of the Americas and the region later known as Canada was undertaken by both French- and English-sponsored sea captains and companies. Borders between French Canada, or Quebec, and British-controlled areas of North America were ill defined and porous. Consequently, explorers and settlers moved freely around North America’s rivers and lakes. French exploration reached as far south as the mouth of the Mississippi River, Pennsylvania, along the Great Lakes, and Lake Champlain. Geography and climate limited the population north of the Great Lakes to fur trappers and fishermen. Both Great Britain and France had difficulties attracting settlers to these northern regions.

The English colonies in New England and Virginia were the fastest-growing regions in which European immigrants were likely to settle because they afforded greater chances of economic success. In fact, the growing economic prosperity of England’s original thirteen colonies did lure an unrecorded number of settlers from the north. In 1745, New Englanders temporarily seized the French settlement and fortress of Louisbourg. Eighteenth century rivalries between Great Britain and France ultimately led to Britain’s successful acquisition of Nova Scotia from France and the expulsion of an estimated 18,000 French-speaking Acadians to Britain’s Atlantic colonies between 1755 and 1763 and. after France’s withdrawal from North America in 1763, to Louisiana. The Acadian French of Louisiana were the first major immigration wave into the future United States from what would eventually become Canada.

Immigration, 1776-1867

The independence of the United States in 1783 led to the emigration from the United States to British North America of more than 35,000 United Empire Loyalists. Britain’s Constitutional Act of 1791 split Quebec into territories named Upper and Lower Canada, each with its own assembly and council elected by its own people. The creation of the Hudson Bay Company to undertake fur trapping and settlement in the western regions of North America was accompanied by the granting of increased political rights for Canadian settlers, thereby lessening the desire of British subjects to go to the United States.

French-speaking Acadians who were expelled from Nova Scotia by the British in 1755. Many of them immigrated to Louisiana, which was then under Spanish rule, and contributed to the development of Cajun culture. (Francis R. Niglutsch)

The unsuccessful attempts by the United States during theWar of 1812 to annex Upper and Lower Canada significantly strained relations between the neighboring countries and limited population movements from either direction. The Rush-Bagot Agreements of 1817 and 1818 demilitarized the border between the United States and Canada, permitting free and mostly unrecorded movements of people between the two countries. Low-cost land grants in 1815 to spur Canadian settlement proffered an economic boom that lasted several decades and attracted more than 800,000 immigrants to Canada between 1815 to 1850, in what has been called the Great Migration. Other nineteenth century developments that lessened incentives for Canadian settlers to move to the United States included the discovery of gold in the territory now known as British Columbia in 1858 and the building of canals and railroads connecting the different parts of British North America.

Records kept by Canada’s Office of Immigration Statistics show that only 209 people immigrated to the United States from Upper and Lower Canada and Newfoundland in the year 1820. Over the ensuing decade, 2,277 more Canadians made the move. The rate of British immigration to the United States from those territories increased in the succeeding decades, with 13,624 making the move during the 1830’s, 41,723 during the 1840’s, and 59,309 during the 1850’s, the decade preceding the U.S. Civil War.

Immigration, 1867-1900

The U.S. CivilWar severely strained relations between the United States, Great Britain, and Canada, which was still called British North America. Union blockades of Southern shipping during the war denied British textile factories the cotton they needed to operate. British attitudes toward immigrating to the United States changed after 1865, as the rapid industrialization of the country began generating a higher volume of manufacturing jobs that needed workers. The U.S. Census of 1870 recorded that 478,685 immigrants from British North America were living in the United States. The majority of them settled in Massachusetts, New York State, Michigan, Maine, Vermont,Wisconsin, and Illinois. Each of these states bordered Canada, making frequent movements back and forth easy.

In 1867, the British North American Act officially created the Dominion of Canada. At that time, Canada had four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. The act created a federal government in Ottawa and provided a process to admit future provinces into the Canadian confederation. Although Canadians continued to move to the United States in succeeding decades, larger numbers of people from other parts of the world were immigrating into Canada to take advantage of inexpensive land in the western regions and to search for gold in the YukonTerritory.

The U.S. Census of 1880 listed 697,509 immigrants from British North America living in the United States, with the states of Massachusetts, Michigan, and New York their principal destinations. In 1890, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, and Maine were the principal residences of the 978,219 immigrants from Canada and Newfoundland in the United States. Canadians were particularly drawn to U.S. states along the border that were rapidly industrializing.

In 1900, the U.S. Census divided Canadian immigrants into English- and French-speakers. Englishspeaking immigrants numbered 747,050 and lived principally in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, and Illinois, all industrial states. French-speakers numbered 439,950, with Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and California their principal destinations.

Immigration from Canada, 1820-2008

Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2008. Figures include only immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status. Data from before 1911 are from British North America; data after 1911 include Newfoundland.

French Canadians in New England

Between 1900 and 1950, U.S. Census figures showed a substantial migration of French Canadians to the United States. The 1900 census recorded that 439,950 immigrants from Quebec were living in the United States, principally in New England. Many were motivated to emigrate because of a long history of discrimination in employment and educational opportunities under British rule. Moreover, raising money to buy farmland in Canada was becoming increasingly difficult. By contrast, employment opportunities in the United States were expanding in thetextile, shoe-making, and lumber industries throughout the Northeast. California’s expanding trade with Asia, the lure of mining jobs, and less expensive land to farmlured French Canadians to the West Coast of the United States. The first half of the twentieth century witnessed a large influx of French Canadians into New England, which was home to 371,928 of them in 1910, to 300,703 in 1920, to 342,075 in 1930, and to 381,302 in 1940.

French Canadians also continued to settle in U.S. states bordering Canada, with Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Michigan, Maine, and New York their principal destinations. U.S. Census records from1910, 1920, and 1930 divided Canadian immigrants into four categories:

- Newfoundlanders (Newfoundland was not part of Canada until 1949)

- Canadians

- Other Canadians

- French-speaking Canadians

During the year 1910, 1,934 Newfoundlanders were living in the United States, along with 784,063 “Other Canadians,” and 23,089 listed as Canada along with 371,928 French-speakers. The U.S. Census for 1920 recorded 7,562 Newfoundlanders, 121,805 Canadians, 693,773 Other Canadians, and 300,712 French Canadians. The 1930 U.S. Census, taken during the first year of the Great Depression, listed 25,283 Newfoundlanders, 52,562 Canadians, 872,133 Other Canadians, and 342,072 Frenchspeakers. The increase in Canadians moving to the United States can be explained by the migrants’ need to find work during the growing international financial crisis.

After Great Britain entered World War II in 1939, many Canadians were drafted into the military to fight; others went to the United States to find jobs in the expanding American war-based economy. The 1940 U.S. Census counted 21,301 Newfoundlanders, 742,358 “Canadians” (“Other Canadians” and “Canadians” were combined), and 273,086 French Canadians living in the United States. As Canadian involvement in the war intensified, civilian and military job opportunities increased, and the numbers of Canadians going to the United States declined. The New England states of Massachusetts, Maine, and New Hampshire continued to attract the largest numbers of French-speaking Canadians.

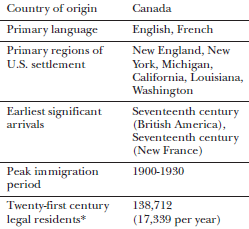

Profile of Canadian immigrants

* Immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status in the United States.

Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2008.

* Immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status in the United States.

Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2008.

In parts ofNewEngland in which French Canadians took up residence, new French-speakingRoman Catholic parishes were created with their own parochial schools, French-language newspapers were published, and French-owned businesses established. Through several generations French Canadian culture was preserved in neighborhoods that were essentially French-speaking enclaves. Members of New England’s French-speaking communities continued to move back and forth freely between the United States and Canada, as bordercrossing documents have recorded. Most Newfoundlanders who entered the United States between 1910 and 1940 resided in Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, New York, and in 1930 in Arkansas. Canadians other than French-speakers and Newfoundlanders were principally located in New England, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Colorado, New Jersey, Washington, California, and Texas.

Immigration After 1945

After World War II ended in 1945, Canadian immigration to the United States began a steady decline. Historically, the movement of Canadians to the United States had been based on the need for jobs and better pay since the seventeenth century. The U.S. Census of 1950 no longer separated immigration statistics for Newfoundland, which had become a Canadian province. That census was also the last to distinguish French-speaking and other Canadians. The number of French Canadians in the United States in 1950 was 159,187. As before, they principally resided in Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, and California. The number of “Other Canadians” in the United States who were recorded in the 1950 census numbered 321,097, with Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire, and Michigan their principal places of residence. U.S. Census tabulations over the next four decades showed 377,952 Canadian-born residents of the United States in 1960, 413,310 in 1970, 169,030 in 1980, 156,938 in 1990, and 191,987 in 2000.

The decline in Canadian immigration after World War II was caused by a number of factors. After the war, Canada pursued more independent policies in foreign and domestic policies. During the early 1970’s, Canada became a haven for VietnamWar protestors from the United States. Meanwhile, increasing numbers of American companies were establishing subsidiaries in Canada that made it less necessary to go to the United States to find automobile and other manufacturing jobs. Canada’s less costly universal health care system insured all Canadians for life—a sharp contrast with the health care system in the United States. Canada has increasingly developed its own national identity, separate from those of the United States and Great Britain. Canadian federal legislation has tended to foster policies that reflect Canadian innovations, greater tolerance of diversity, and a global agenda more compatible with the European Union than with the United States. All these developments have tended to make emigrating to the United States less attractive to Canadians.

Aparallel decline in the migration of French Canadians to the United States after World War II has been due, in part, to the Canadian government’s granting of more political autonomy to Frenchspeaking Quebec. This change has made it easier for French-speaking Canadians to preserve their language, culture, and Roman Catholic faith—all of which would be threatened if they were to move to the English-speaking United States.

At the same time, the decline of the shoe, textile, and logging industries in New England and other U.S. border states has lessened the attractions of emigrating.

Twenty-first Century Trends

Population movements between Canada and the United States have been influenced by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that Canada, the United States, and Mexico signed in 1993. NAFTA significantly reduced trade barriers between Canada and the United States and made it much easier for Canadians to work in the United States on temporary visas. In 2006, 64,633 Canadians were working in the United States on temporary employment visas, and another 13,136 were in the United States as their dependents. In contrast, during that same year, 24,830 U.S. citizens worked in Canada on similar temporary visas.

The U.S. Congress’s passage of the Patriot Act in 2001, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, started a process that increasingly tightened border controls between Canada and the United States. Later amendments to the law for the first time began requiring people crossing the U.S.- Canadian border, in either direction, to carry passports. Heightened security at border crossings has entailed closer scrutiny of travelers and more frequent searches of vehicles, creating unprecedented delays and increased stress—all of which has made border crossings less convenient.

Despite the decline in Canadian immigration to the United States, Canadians have continued to see their southern neighbor as a land of greater economic opportunities, though to a lesser degree than in earlier years. Many Canadian athletes, actors, broadcasters, artists, writers, and corporate executives have continued to work in the United States, where their talents reach larger audiences and markets and where they earn higher incomes than they can in Canada.

William A. Paquette

Further Reading

- Brault, Gerard J. The French-Canadian Heritage in New England. Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1986. Detailed history of New England’s third-largest ancestry group.

- Doty, C. S. The First Franco-Americans: New England Histories from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1938-39. Orono: University of Maine at Orono Press, 1985. Comprehensive history of French Canadian immigration and experiences in the United States, based on oral histories collected during the 1930’s.

- Faragher, John Mack. A Great and Noble Scheme. New York:W.W. Norton, 2005. History of the Acadian French, many ofwhomimmigrated to Louisiana.

- Hamilton, Janice. Canadians in America. Minneapolis: Lerner, 2006. Brief survey of Canadian immigration to the United States, emphasizing the years after 1860.

- Ramirez, Bruno. Crossing the Forty-ninth Parallel. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2001. Detailed study of Canadian immigration to the United States between 1900 and 1930.

- Schideler, Janet L. Camille Lessard Bissonnette: The Quiet Evolution of French-Canadian Immigrants in New England. New York: Peter Lang, 1998. Narrative of personal histories among New England French Canadians.

- Wade, M. The French Canadians, 1760-1967. Toronto: MacMillan, 1968. Comprehensive history of French Canadians.

See also: Canada vs. United States as immigrant destinations; Hayakawa, S. I.; History of immigration, 1620-1783; History of immigration, 1783-1891; History of immigration after 1891; Jennings, Peter; Louisiana; New York State; North American Free Trade Agreement; Patriot Act of 2001; Vermont.

- People

- Immigrant groups

- Labor

- Nativism

- Civil rights and liberties

- Cities

- Culture

- Refugees and displaced persons

- Court cases

- Illegal immigration

- Advocacy organizations and movements

- Health

- Arts and music

- European immigrants

- Anti-immigrant movements and policies

- African immigrants

- Citizenship and naturalization

- States

- Asian immigrants

- Agricultural workers

- Children

- Immigration reform

- Laws

- East asian immigrants

- Borders

- Deportation

- Events and movements

- International agreements

- Mexican immigrants

- Education

- Emigration

- Theories

- Ethnic enclaves

- Latin american immigrants

- Business

- Science and technology

- Government agencies and commissions

- Politics and government

- Family issues

- Women

- Economic issues

- Southeast asian immigrants

- Canadian immigrants

- Push-pull factors

- Transportation

- Slavery

- Philanthropy

- Religion

- Demographics

- Research

- Assimilation

- Literature

- Subversive and radical political movements

- Communications

- Journalism

- Language issues

- Crime

- Violence

- Military

- Wars

- Law enforcement

- West indian immigrants

- Stereotypes

- Symbols

- Land

- Psychology

- South and Southwest Asian immigrants

- Pacific Islander immigrants

- Colonies and colonial regions

- Legislation and regulations

- Canada

- United States

- War and immigration

- Administration

- Hispanic issues and leaders

- Treaties

- Economics and commerce

- Immigration policy

- Religion

- Colonial founders and leaders

- Explorers and geographers

- France

- Political figures: Canada

- Political figures: United States

- Race and ethnicity

- Reformers, activists, and ethnic leaders

- Women