Criminal immigrants

2011-09-30 03:08:33

Definition: Aliens who enter the United States with criminal records, or those who commit crimes after arriving in the United States

Significance: Over time the federal government has passed numerous laws and increased enforcement efforts to thwart the entry of criminal immigrants and to make it easier to deport alien criminals who are in the country, including those who have committed their crimes after arriving. During the late twentieth century, the list of criminal activities for which aliens could be deported was expanded greatly, increasing arrests and detentions and driving up costs to the government for carrying out enforcement activities.

Immigrants who committed crimes in other countries have been entering the United States since the first Europeans began arriving in the colonies during the early seventeenth century. However, many early immigrants were considered “criminals” simply because poverty had driven them to break harsh European laws that made seemingly petty crimes such as stealing bread, pickpocketing, and vagrancy felony offenses. Consequently, many socalled felons who immigrated to America were actually merely petty criminals.

After the United States became independent in 1783, federal government officials were lax in dealing with criminal immigrants. However, the great waves of newcomers arriving from Europe after the 1820’s spurred more aggressive efforts, first by the individual states and eventually by federal authorities, to bar persons with criminal records from entering the country and to detain and deport immigrants who committed crimes after arriving in the United States.

Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Initiatives

National immigration policy was slow to develop after independence. Initially each state was responsible for overseeing foreign immigration. Most states had laws prohibiting criminals from gaining admittance, but these laws were so loosely enforced that many foreigners with criminal records in their home countries entered the United States legally. In 1875, the federal government finally entered the effort to prohibit immigration by criminals by passing the Page Law, which restricted entry of “undesirables,” particularly from China. The U.S. Congress took stronger steps in 1882, and in 1891 the federal government empowered the new office of the Commissioner for Immigration to oversee all immigration. This office was specifically directed to take measures to turn away criminals at ports of entry. Generally, aliens found already to have criminal records or to have engaged in criminal activities within one year of their arrival in the United States could be deported. The Immigration Act of 1907 extended the period from one to three years to give the government more time to deal with those discovered to be criminals.

Despite these new laws, lax enforcement continued to permit many immigrants with criminal records— especially those from Italy—to enter the United States. Many criminal Italian immigrants would eventually form the nucleus of what would become known as the Mafia. As the federal government became more aware of the kinds of individuals who were slipping past immigration officials, a serious proposal was made to require all Italian immigrants to obtain certificates of good character from the local police chiefs in their hometowns. This proposal died when government officials realized it was unenforceable. In any case, criminal activity was not restricted to immigrants coming from Italy. Frequently, when persons apprehended in the United States for criminal activities were determined to be recent immigrants, or to have entered the country illegally, they were deported, in addition to other criminal penalties that may have been imposed when they were convicted of their crimes.

High-Profile Immigrant Criminals

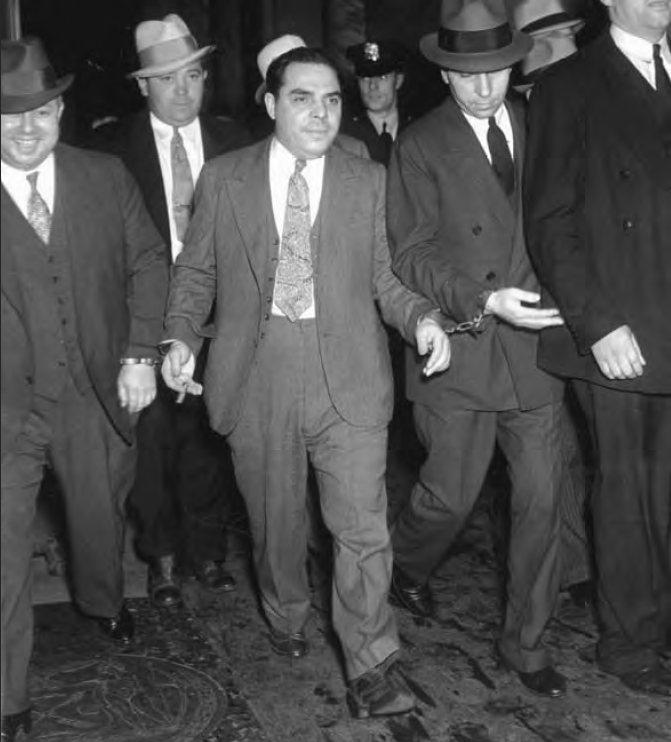

The U.S. government has often used its power to deport undesirables as a means of ridding the country of notorious criminal immigrants. In some cases, deportation was used to guarantee that the person would no longer be able to pursue criminal activities in the United States. For example, deportation procedures were used to remove a number of important Mafia figures. One of the most notable Mafia figures was Salvatore Luciana, best known in America as Charles “Lucky” Luciano. The first Mafia leader caught engaging in widescale sales of illegal drugs, Luciano was returned to Sicily as part of a plea-bargain agreement in 1946. Another key Mafia leader, Carlos Marcello of New Orleans, was deported to Guatemala in the 1950’s. However, he later managed to return to the United States to resume his criminal activities.

Sicilian-born mobster Charles “Lucky” Luciano leaving a New York court appearance in 1936, when he received a long prison sentence for running a prostitution ring. He was paroled in 1946 on the condition that he return permanently to Sicily.He never came back to the United States but later tried to run criminal activities in the United States from Cuba. ( AP/Wide World Photos)

Sicilian-born mobster Charles “Lucky” Luciano leaving a New York court appearance in 1936, when he received a long prison sentence for running a prostitution ring. He was paroled in 1946 on the condition that he return permanently to Sicily.He never came back to the United States but later tried to run criminal activities in the United States from Cuba. ( AP/Wide World Photos)

Another category of criminal immigrants who received significant publicity after World War II were those generically classified as Nazi war criminals. These included officials of the Nazi Party and other persons who helped manage concentration camps in which millions of innocent civilians were massacred during the Holocaust. During the decade following the end of the war, many of these people—including citizens of other countries who assisted the Nazis—managed to slip out of their homelands and escape to other nations. Many of these people evaded detection for decades. In 1973, the first suspected war criminal to be extradited from the United States to Germany to stand trial for war crimes was Hermine Braunsteiner. A guard at Majdanek and other women’s prisons, she had married an American serviceman after the war.

In 1979, the U.S. Justice Department established the Office of Special Investigations to help root out Nazi war criminals living in the United States. Among the more famous criminals identified and deported was John Demjanjuk, who had been known during the war as “Ivan the Terrible” for his savage treatment of prisoners at Treblinka. In almost all cases, the U.S. government took the position that anyone who—like Demjanjuk and Braunsteiner—had obtained U.S. citizenship after having participated in the extermination of innocent citizens abroad had done so under false pretenses and was therefore eligible for deportation.

Obstacles to Deportation

Despite strong government efforts to apprehend and deport war criminals, lengthy court battles have frequently permitted many war criminals to remain in the United States for long periods. Additionally, efforts to deport immigrants with criminal records have not always gone smoothly. In 1980, Cuban leader Fidel Castro authorized the emigration of all Cuban citizens wishing to go to the United States. In a mass exodus that became known as the “Mariel boatlift,” more than 100,000 Cubans left their homelands on boats from the port of Mariel. Among them were nearly 8,000knownprostitutes, criminals, and persons judged criminally insane whom Castro had released from prison and directed to leave the country. After U.S. authorities became aware of the large criminal element entering the country as a result of this supposedly humanitarian effort, a massive search was mounted to track down everyone who had entered the country in the boatlift. Federal officials detained thousands of Cubans until their backgrounds could be checked. Eventually most of the Cuban criminals were sent back to Cuba. However, detentions of innocent immigrants— some of whom were detained as long as five years—led to two riots at prisons in the southern states in which the detainees were held.

“Ivan the Terrible?”

Accused war criminal John Demjanjuk (center) in 1986, after being deported to Israel, where he was convicted of having been the notorious “Ivan the Terrible” in the Treblinka concentration camp during World War II. After his conviction was overturned on the basis of reasonable doubt in 1993, he was returned to the United States, only to face new charges of having served in Nazi death camps. In 2005, the United States tried to deport him again, but no country would accept him. In 2009, however, he was deported to Germany to stand trial on nearly 28,000 counts of being an accessory to murder. (AP/ Wide World Photos)

Accused war criminal John Demjanjuk (center) in 1986, after being deported to Israel, where he was convicted of having been the notorious “Ivan the Terrible” in the Treblinka concentration camp during World War II. After his conviction was overturned on the basis of reasonable doubt in 1993, he was returned to the United States, only to face new charges of having served in Nazi death camps. In 2005, the United States tried to deport him again, but no country would accept him. In 2009, however, he was deported to Germany to stand trial on nearly 28,000 counts of being an accessory to murder. (AP/ Wide World Photos)

Illegal Immigration and Criminal Activity

Although immigrants in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were occasionally driven to criminal activity, the ready availability of jobs in America’s rapidly expanding industrial economy usually meant that new arrivals could become economically independent relatively quickly. However, similar opportunities were not available to immigrants arriving after World War II, especially during the 1980’s and 1990’s. By then the American economy had changed radically, and the lack of preparedness among many new immigrants for the new knowledge economy created a permanent underclass willing to work for minimal wages. The presence of this growing group fueled new fears among the general population, who were already skeptical of newcomers who were perceived as contributing little to the country’s prosperity. These concerns led to the enactment of a new round of restrictive policies, often couched in terms of weeding out criminal elements among immigrant populations.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the bulk of “criminal” immigrants in the United States were Mexicans. Mexican immigration had been an issue since the early twentieth century. In 1924, the U.S. government took steps to limit immigration fromMexico, passing a law that made it a misdemeanor to gain entry illegally; second attempts at entering illegally after deportation were considered felony offenses. During the 1970’s, the federal government began passing tougher laws that treated illegal immigrants as felons. Consequently, thousands of immigrants with no criminal records in their homelands who happened to enter the United States without documentation became instantly branded as criminals upon their arrival. At the same time, the federal government began stronger enforcement efforts to capture, detain, and deport those who had crossed the nearly twothousand- mile border between Mexico and the United States without proper documentation.

Meanwhile, federal efforts to limit legal immigration from Mexico made possible a flourishing criminal business in human trafficking. Networks sprang up to help thousands of people who could not qualify for legal entry into the United States get across the border, where they could find work in agricultural, construction, and manufacturing businesses desperate for cheap labor. The smuggling of illegal immigrants thus created criminal subcultures on both sides of the Mexican border.

Compounding the problem of illegal immigration from Mexico was the growth in drug smuggling across the border.Anumber of those crossing into the United States were actively participating in the drug trade, which was built on a sophisticated network run by cartels in Central and South America. During the 1980’s the federal government began cracking down on this illegal drug trade, and a high percentage of those arrested for drug violations turned out to be illegal immigrants. Efforts to curb the inflow of drugs into the United States dovetailed with increased efforts to round up and deport illegal immigrants, under the assumption that reducing the number of illegal immigrants in the country would decrease the number of those involved in criminal activities involving illicit substances.

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996

In 1996, the federal Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act further stiffened penalties for both illegal and legal immigrants. Under its provisions, immigrants who had entered the United States legally could be arrested and deported for certain crimes they may have committed as long as a decade earlier. In addition to felonies, crimes for which deportation was permissible were drug use and sale, domestic violence, and even drunk driving. All persons who entered the country without proper documentation were subject to immediate deportation, and immigration officials did not have to obtain permission from judges to carry out this action. Moreover, it became a felony for a deported alien to reenter the United States within ten years of deportation. The Immigration and Naturalization Service was expanded to provide more agents to track down undocumented immigrants, who were handled as criminals.

At the end of the twentieth century, a high percentage of inmates in federal prisons were immigrants who had been arrested and were being held for entering the country illegally, but who had committed no other crime. At the same time, gangs in many metropolitan areas contained large populations of illegal immigrants. While apprehension and deportation of these individuals became a priority for the U.S. government, the porous border between the United States and Mexico made it easy for recently deported persons to sneak back into the United States.

After the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington of September 11, 2001, the U.S. government stepped up efforts to find and deport undocumented aliens, especially those of Middle Eastern descent and Muslims of all nationalities. Although the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the right of immigrants to due process under the U.S. Constitution, provisions of the 2001 Patriot Act strengthened the power of immigration officials wishing to use detention and deportation as tools to rid the country of immigrants judged to be a security risk.

The cost of dealing with criminal activity attributable to immigrants is often hard to calculate. Best estimates in the early years of the twenty-first century indicated that expenses for enforcement operations, court systems, and incarceration facilities were running into billions of dollars annually.

Laurence W. Mazzeno

Further Reading

- Brotherton, David C., and Philip Kretsedemas, eds. Keeping Out the Other: A Critical Introduction to Immigration Enforcement Today. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. Collection of essays investigating the federal government’s attempts to control immigrant populations through a series of laws that consistently expanded the number of crimes for which deportation was permissible.

- Finckenauer, James O., and Elin J.Waring. Russian Mafia in America: Immigration, Culture, and Crime. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998. Describes activities of criminal elements among Russian immigrants, compares their activities to elements in other immigrant groups, and describes efforts of law enforcement to deal with these criminals.

- Martinez, Ramiro, Jr., and Abel Valenzuela Jr., eds. Immigration and Crime: Race, Ethnicity, and Violence. NewYork:NewYork University Press, 2006. Collection of essays exploring the causes for criminality among immigrants. Includes discussions focusing on behavior of specific ethnic groups in several major American urban centers. Provides an extensive list of sources for further study.

- Ryan, Allan A., Jr. Quiet Neighbors: Prosecuting Nazi War Criminals in America. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984. Study of the U.S. government’s efforts to identify and extradite or deport Nazi war criminals, compiled by a member of the Justice Department’s Office of Special Prosecution.

- Waters, Tony. Crime and Immigrant Youth. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1999. Sociological study that attempts to account for cultural and sociological factors influencing criminal behavior of young members of immigrant communities. Traces the history of crimes committed by youthful immigrants in America.

See also: Crime; Deportation; Drug trafficking; Godfather trilogy; Illegal immigration; Mariel boatlift; Ponzi, Charles; Russian and Soviet immigrants; Smuggling of immigrants; Stereotyping; “Undesirable aliens.”

- People

- Immigrant groups

- Labor

- Nativism

- Civil rights and liberties

- Cities

- Culture

- Refugees and displaced persons

- Court cases

- Illegal immigration

- Advocacy organizations and movements

- Health

- Arts and music

- European immigrants

- Anti-immigrant movements and policies

- African immigrants

- Citizenship and naturalization

- States

- Asian immigrants

- Agricultural workers

- Children

- Immigration reform

- Laws

- East asian immigrants

- Borders

- Deportation

- Events and movements

- International agreements

- Mexican immigrants

- Education

- Emigration

- Theories

- Ethnic enclaves

- Latin american immigrants

- Business

- Science and technology

- Government agencies and commissions

- Politics and government

- Family issues

- Women

- Economic issues

- Southeast asian immigrants

- Canadian immigrants

- Push-pull factors

- Transportation

- Slavery

- Philanthropy

- Religion

- Demographics

- Research

- Assimilation

- Literature

- Subversive and radical political movements

- Communications

- Journalism

- Language issues

- Crime

- Violence

- Military

- Wars

- Law enforcement

- West indian immigrants

- Stereotypes

- Symbols

- Land

- Psychology

- South and Southwest Asian immigrants

- Pacific Islander immigrants

- Colonies and colonial regions

- Legislation and regulations

- Canada

- United States

- War and immigration

- Administration

- Hispanic issues and leaders

- Treaties

- Economics and commerce

- Immigration policy

- Religion

- Colonial founders and leaders

- Explorers and geographers

- France

- Political figures: Canada

- Political figures: United States

- Race and ethnicity

- Reformers, activists, and ethnic leaders

- Women